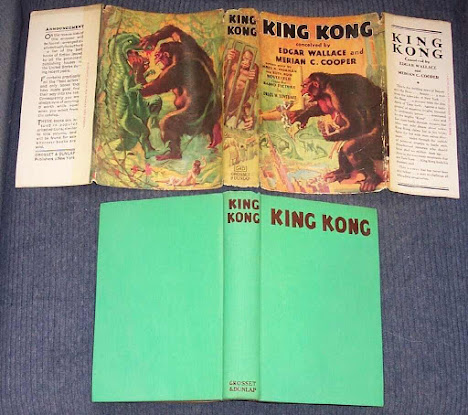

The 1932 novelisation of Merian C. Cooper's King Kong

Edgar Wallace didn’t write any of Kong, not one bloody word. (Merian C. Cooper)

The Photoplay

I have long been a fan of the original 1933 King Kong movie - not a big fan, mind you, but a fan nevertheless. I had purchased the Peter Jackson-sponsored remastered DVD in 2005 and Blu-ray in 2019, and back in the eighties picked up a Macfarlane model of Kong chained and bound on the New York theatre stage. Unfortunately I had long ago lost the accompanying Ann Darrow / Fay Wray figure. I cannot remember when I first saw King Kong - probably on TV back in the 1960s, as a kid. I don't think I have ever seen it on the big screen, which is a shame, as I do remember seeing Frankenstein at the Regent Theatre, Wollongong, in the 1970s, and that was a memorable experience. But I know that I returned to King Kong every now and then over the years, as it was on my list of classics, alongside Metropolis, Forbidden Planet, Apocalypse Now, Jason and the Argonauts, Lost in Translation and a few others. I wasn't into 'monster' movies generally, and abhor horror such as The Exorcist and even Alien. However, I am drawn to the early black and white Universal horror of the 1930s, such as The Mummy and Frankenstein, and my interest in movie posters inevitably, and recently, led me not only back to them, but also to King Kong. It was therefore with some surprise that late in 2019 I came across a contemporary novelisation of the film - something I had never considered as it appeared to me to be such an original piece of movie magic, with no real antecedents, apart from 1925's The Lost World.

So it was that, following some initial research, I discovered that in 1932 a certain Delos W. Lovelace (1894-1967) was commissioned by his old friend Merian C. Cooper (1893-1973) to turn the script of the forthcoming RKO Radio Pictures release of King Kong into a work of fiction for public consumption and promotion alongside the film (Lovelace 1932, Wikipedia 2020). For this, he was paid $600 (Morton 2005, Mullis 2017). Lovelace was a writer of short stories and reporter for the New York Daily News and New York Sun in the 1920s. He had written a number of articles and two biographies prior to King Kong, including one on Admiral Byrd and his recent polar expedition (Lovelace 1930). This undoubtedly assisted in bringing him to the attention of the producers and directors of the film, namely Cooper - himself an experienced adventurer - and his partner and cinematographer Ernest B. Schoedsack (1893-1979). The former had for a number of years been working on a treatment concerning a big ape running amok in New York, though script development of King Kong did not begin in earnest until the end of December 1931 when the studio gave the production the green light. Thereafter it progressed with numerous changes through the first half of 1932, culminating in the commencement of substantial filming with the cast in August. Even then, the script was in a state of flux and in many ways evolved to accommodate the complex, and innovative, technological aspects. All told, King Kong was in production for a period of some fifty-five weeks, through to early 1933. Thus was not normal. The special effects work by Willis O'Brien and his team was a tedious process and continued to the beginning of the new year. Reflecting this lengthy period of development, filming and editing, at least five different versions of the script - from scenario to shooting script - survive in the RKO Archives at the University of California - Los Angeles, with substantial differences between the first and last (Glashen 2019).

A number of writers over the years have attempted to analyse the origins and evolution of King Kong using archival records and subsequent interviews with the people involved. It is a complex tale, though the role of Lovelace in amongst this task was simple enough - he was paid to, just release three months out from the film's premiere, produce a novelisation in order to generate interest. He therefore made use of the 'final' script by Ruth Rose, as provided to him through July-October 1932, though even that varied from the film as eventually distributed. For example, the famous lost 'spiders in the pit' scene was cut very early, along with a number of other more violent, and less dramatic, character development and narrative exposition elements. Cooper felt it important to juxtapose Kong's naked brutality with his protective treatment of Ann Darrow above all others. As a result, Lovelace was able to produce a readable novelisation which contained action, romance and adventure. He did a more than competent job in fleshing out the script as provided to him. It is likely that, as part of that process, he also liaised with some of those intimately involved in the production, including, most importantly, Cooper and Rose. The latter, it has been noted, ultimately came up with ninety percent of the final dialogue and added a decided sense of reality to the story as presented on film. Lovelace/s King Kong novelisation was published in December 1932, ahead of the film’s premiere the following March and general release during May 1933. It's authorship was variously attributed to (alphabetically): Merian C. Cooper, James A. Creelman, Delos W. Lovelace, Ruth Rose and Edgar Wallace.

The hardback book (there was no initial paperback version) was printed in octavo size (8vo – 5 ¾ x 8 ¼ inches) by the firm of Grosset & Dunlap, New York, specialists in the production of photoplays during the silent and early sound era (Wikipedia 2020). A typical photoplay would comprise a previously published book, or short story, upon which a film – then also known as a photoplay - was based, or a newly written novelisation was created around the final script as shot. The latter was the case with the Lovelace King Kong. Though the term photoplay is no longer used, such practices had been associated with the earliest days of cinema in the late 1890s and continue through to the present day. For example, hardback, paperback and magazine serialised novelisations of the 1927 German silent film Metropolis appeared during 1926-7. Alan Dean Foster’s 1976 novelisation of George Lucas’s Star Wars and Ridley Scott's Alien in 1979 are good examples, as are the Disney corporation's publication of a new version of Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland in 2010 to coincide with the Tim Burton version of that oft filmed classic, and the 2017 novelisation of Kong: Skull Island. The Grosset & Dunlap photoplay series would generally feature a cover which referred to the film, and illustrations – usually still photographs – interspersed throughout, or as end papers. The latter was the case with King Kong.

|

| End papers from the 1932 novelisation of King Kong. |

In some instances, individual artworks, such as original paintings or drawings related to the film, would be included, as was the case with the 1937 ‘Author’s Edition’ of James Hilton’s Lost Horizon, also published by Grosset & Dunlap (Hilton 1937). The original photoplay for that film merely included illustrated end papers, while the Author's Edition contained watercolour illustrations of characters and costumes that had been prepared for the film.

Few, if any, original photoplays

have ever been recognised for their literary worth. In most cases they

disappear quickly amongst the fandom following the initial release of the film, reflecting, in many instances, the ephemeral nature of the films themselves. For example, Lon Chaney's 1927 London After Midnight no longer survives, though copies of the photoplay novelisation do. The Lovelace King Kong is an exception to this short-term, ephemeral nature, judging by the number of times it

has been reprinted (refer listing below). This first took place in 1965, some 33 years after the original edition, and following an increase in fandom as part of the burgeoning pop culture during the 1960s. Since then it has remained in print, though reprints have usually appeared in association with remakes of the film - for example, in 1976 and 2005 - rather than as a result of the literary

merits, or lack thereof, of the book itself. Interest in the film, and an ever growing fan base, spurred on by the activities of individuals such as the American Forrest J. Ackerman, have also been drivers towards reissue of the text.

In some instances the success of

a film overtakes the success of its literary precursor. For example, the aforementioned Lost Horizon, first

published in 1933, the same year as the premiere of King Kong, was a slowly forming literary success, spurred on by the awarding

of the British Hawthornden Prize in 1935. This brought it to the attention of Hollywood director Frank Capra. His stunning movie adaptation of 1937 has been identified as a

rare example of a film bettering the book upon which it is based. As a result, Capra’s

production is now recognised as a classic of the genre, while Hilton’s original

novel remains in the background, though still in print. Examples exist where the

photoplay novel which derives from a script stands alone. This is the case, for example,

with Thea von Harbou’s Metropolis,

published in Germany at the end of 1926, some three months before the Berlin premiere of the

film in January 1927 (Von Harbou 1926). Von Harbou and her then husband and film director Fritz Lang had worked on

development of the script since the middle of 1925. Von Harbou was both script writer

and novelist, such that when it came time to commission a fictional account of the film –

a photoplay – for promotional purposes and serialisation in support of the movie's forthcoming release, she was a natural pick for the task. What she produced, however, was

something which was in many ways different to the script and yet intimately

connected to it. Her novel is a literary work with its own identity - a

romantic fantasy in the Germanic tradition - whereas Lang’s film has been

criticised for being too technical, reliant on the visuals and having no heart - a heart which is to be found within the novelisation. In other instances, the

original literary work and the film both attain classic status. We have this

with, for example, Harper Lee’s 1960 To Kill

a Mockingbird and J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1954-5 The

Lord of the Rings trilogy. Subsequent movie adaptations respected their literary

origins and did not sway too far from the authors intent. One was directed by

Robert Mulligan, starred Gregory Peck and was released in 1962; the other was directed

by Peter Jackson, filled with relatively unknown actors and premiered during 2001-3. It is unfortunate that Peter Jackson was not as successful in his

adaptation of King Kong in 2005,

though in that instant he and his scriptwriters were relatively free to adapt

the original 1933 shooting script, rather than relying on the ‘definitive’

novelisation by Delos W. Lovelace.

All in all, the fate of published photoplays has generally been one of short-term interest followed by long term neglect and intermittent fandom interest. The

literary value of such works, if present, is usually recognised, though

photoplays primarily remain mere artifacts of the film from which

they were derived. It is often the case that fans of a movie look to a novelisation

to flesh out what they saw on the screen. In many instances that fleshing out

is merely a rewriting of the script and offers nothing new in the way of plot or character development. In other

cases, as with von Harbou’s Metropolis,

the novelisation is worth reading for the additional elements

which enhance the viewing experience and also provides a tangible record of the film's narrative. In the case of Star Wars, a whole canon of fan fiction has developed since its first appearance in 1976. This can also be seen in the

case of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the

Rings trilogy, though in a different form. Tolkien’s original 600,000-word, 3-volume work of fiction is dense and

was never able to be presented in toto on screen. Jackson and his team did a

good job with the initial release which ran over 8 ½ hours, and with the

subsequent extended version which added an additional 2 hours. Of course, those

fans who wanted more, merely had to go back to the original, classic text to delve into the almost limitless detail of Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium through publications such as The Silmarillion (1977). For King Kong there was only ever the film and novelisation.

Developing the shooting script

The King Kong novelisation of 1932, just like the movie released the following year, was, according to text on the dust jacket cover, conceived by Merian C. Cooper and then RKO script writer Edgar Wallace (1875-1932), with the screenplay further developed by James Armstrong Creelman and Ruth Rose, the wife of Ernest B. Schoedsack. All of these names were noted on the cover of the novelisation, along with the attribution to Delos W. Lovelace at the bottom. However, that list does not present a true picture of the origin, and ultimate development, of the movie King Kong as seen by the public at large. As Rudy Behlmer pointed out in 1976, Merian C. Cooper had, according to an interview in 1965, developing the story during 1929-30 (Gottesman and Geduld 1976). Subsequent to that, various individuals were brought in by the studio to help bring the film version to the screen and, in the case of the novelisation, to public attention. One of those was English novelist Edgar Wallace, who David O. Selznick, then head of RKO, convinced Cooper should be involved because of the reputational gravitas he would bring to the project. Ultimately that is all Wallace did bring, and nothing more - not a single word or idea. Lovelace was probably brought on board to fulfill the necessary writing duties following the sudden death of Wallace on 10 February 1932 from undiagnosed diabetes and pneumonia (Campbell 2015, Wikipedia 2020). The English Wallace, who had been engaged by RKO at the end of 1931 to develop both the script and novelisation of King Kong, was a high-rolling heavy smoker and prolific writer of fiction, plays and film scripts. He was one of the most popular author's at that time with some 170 novels under his belt. As such, his name was given prominence over Cooper's upon the novelisation cover and during the original release promotional campaign, where it featured on posters and in newspaper advertisements. One of the latter, from the Vancouver Province of 4 May 1933, and with no mention of Marian C. Cooper, stated:

R.K.O. road show attraction of a startling idea conceived by Edgar Wallace.

Similarly, upon the film's release in Great Britain, it was identified as 'Edgar Wallace's King Kong' within promotional material. Though Wallace only worked with RKO from December 1931 through January 1932, Cooper and RKO were initially hoping that his popularity, reputation and speed as a writer would assist the project by his development of a novelisation and script. It was purely a marketing ploy. The resultant film would carry the label 'based on the novel by Edgar Wallace' and this would supposedly enhance its attraction to the general public. Cooper, however, was responsible for the substantial development of the original idea and draft outline up to the point of Wallace's arrival in the country, having pitched it to Paramount - unsuccessfully - and then RKO, where he was hired as an executive producer in 1931. It appears that Cooper came to regret this deal with Wallace, stating after the film's release:

Edgar Wallace didn’t write any of Kong, not one bloody word. I’d promised him credit and so I gave it to him. (Simpson 2014)

In a letter to Selznick dated 20 July 1932, prior to the film's release and following the death of Wallace, Cooper had stated:

The present script of Kong, as far as I can remember, doesn't have one single idea suggested by Edgar Wallace. If there are any, they are of the slightest... I don't think it fair to say this is based on a story by Wallace alone, when he did not write it, though I recognize the value of his name and want to use it.

Likewise, in a 1965 letter to Cooper, Selznick stated:

I have never believed, and don't believe now, that Wallace contributed anything much to King Kong. But the circumstances of his death complicated the writing credits. (Gottesman and Geduld 1976)

Edgar Wallace arrived in New York at the end of November of 1931, employed by RKO on $3,000 a week. He was immediately tasked with developing new film ideas, along with the editing of scripts for those already green-lighted and writing new ones. It was also suggested that his work with RKO could lead to directing opportunities. As a writer he was prolific, and quick, pumping out articles, short stories, plays and film scripts at an unprecedented rate, and usually with the aid of a Dictaphone. We know this because he wrote letters and kept a diary during his brief time in America, outlining in detail his work ethic and engagement with Cooper on what became King Kong (Wallace 1932). For example, on 8 December 1931, just over a week after arriving in New York, Wallace noted in a letter to his wife Ethel of being asked by Cooper to work on, among other things, 'a story of prehistoric life!' This was perhaps his first introduction to what would become King Kong. By the following day he now had 'four pictures on hand', including the idea put to him of doing a 'prehistoric animals story'. Three days later he watched Cooper shoot some footage of men fighting an unseen beast:

This was part of a reel Cooper and Willis O'Brien were putting together to present to RKO executives in New York in order to get the green light for the production. On 23 December Wallace went with Cooper to the studio animation room:

On Christmas day, after getting approval for King Kong - or the innocuous 'The Eighth Wonder of the World' as the studio would prefer to call it - Cooper rang Wallace and they had a lengthy conversation:

Wallace also dined with Cooper on a number of occasions during this period, discussing numerous issues apart from 'the beast story.' Two days later he commenced work on the Kong scenario, writing, or rather, dictating onto wax cylinders with his Dictaphone machine. These would then be transcribed and typed up by his staff and, ultimately, the RKO stenography department. He noted that this script would be a relatively slow process for him, 'because it is all action'. On the 29th Wallace further noted somewhat tellingly in one his letters to his wife in England:

This comment highlights the fact that Wallace had very little to do with the script as actually shot, as it was very much developed by Cooper and O'Brien, and, ultimately, Ruth Rose who was largely responsible for the day-by-day, on set, script development. The following day Wallace commented on seeing more of the background development work and discussions around the writing of the story / novelisation of Kong, with a by-line for Cooper.

[30 December 1931] I had an appointment with Merian Cooper at 11 o'clock, and we saw a girl for our play. I don't think she will quite do. She's got a contract with Paramount, so it doesn't matter. She was terribly pretty and had a lovely figure, but what we want is a very mobile kind of face that will express horror. We had a long talk about the scenario, which is not yet written but only roughly sketched, and came to a decision as to the opening. We practically know how the story is going to run. There will be a tremendous lot of action in it, but there will also be a lot of dialogue. I saw a length of the film which we might use. R.K.O. was going to produce a prehistoric animal picture and made one or two shots. They were not particularly good, though there was one excellent sequence where a man is chased by a dinosaurus. I went into the animation room and watched the preparation of the giant monkey which appears in this play. Its skeleton and framework are complete. He is, of course, a figure, but a moving figure. You have no idea of the care that is taken in the preparation of these pictures. Cooper insists that every shot he takes shall first of all be drawn and appear before him as a picture. The most important scenes are really drawn and shaded, and they are most artistic. Talking of the care they take, I saw a wood-carver fashioning the skull on which the actual figure will be built. In another place was a great scale model of a gigantic gorilla, which had been made specially. One of the gorilla figures will be nearly thirty feet high. All round the walls are wooden models of prehistoric beasts. The animation room is a projection room which has been turned into a workshop. There are two miniature sets with real miniature trees, on which the prehistoric animals are made to gambol. Only fifty feet can be taken a day of the animating part. Every move of the animal has to be fixed by the artist, including the ripples of his muscles. Of course it is a most tedious job.... I am going to write the story of our beast play in collaboration with Merian Cooper. That is to say, I will give him a "bar line", a bar line being credit as collaborator, because he has really suggested the story, though I of course shall write it, and I am to be allowed to use the illustrations that we are having drawn. It ought to be the best boys' book of the year. He doesn't want to take a penny out of it as long as he has a credit line.

This seemingly magnanimous gesture by Cooper was to have repercussions when Wallace died suddenly in February. Cooper, a man of his word and keen to make use of the Wallace name, stood by the agreement. Wallace was back to work on New Year's Day:

By 3 January Wallace was able to note in his diary:

By the next day Wallace's work was almost done:

It is interesting that the following day Wallace should note the important opportunity King Kong would provide him, if it were successful:

Wallace realised his role in facilitating the transfer to print of Cooper's vision. Though the draft script was 'finished', an alteration was immediately called for by the studio - the first of many:

And some more changes on the 8th:

The following week additional issues arose with the script:

The problem with the title would not go away:

Wallace's script was quickly recognised as a good foundation, and Cooper was very pleased with that:

[15 January 1932] Cooper called me up last night and told me that everybody who had read "Kong" was enthusiastic. They say it is the best adventure story that has ever been written for the screen. It has yet to go past the executive, but I rather fancy there will be no kicks. We haven't yet got the girl. We've got to have a tiny for the part, but the tiny has got to act, and that, I think, is going to be the real difficulty more than the size.

By the end of the week, Wallace was now aware that, with the scenario / script completed, he had another job in front of him:

This indicates that what Wallace had completed to date was merely what Cooper had developed - a shooting script, - and that he had merely recorded it in paper form. Wallace's fulsome 'story' version would never be completed due to his unfortunate demise on 10 February and the fact that the novelisation could now not commence until the script had been finalised - a process that was many months away. Any idea of Wallace quickly publishing a novelisation some 12 months out from the movie's premiere, and upon which the subsequent film would be based, disappeared with his death. The following day he noted:

By this time there was a buzz about the movie, and on 19 January Wallace noted in his diary that, following on the recent success of horror films such as Dracula and Frankenstein:

With his involvement with transcribing the script for King Kong at an end for the time being, on the 20th he turned his mind to another related task:

This, however, was not to be. Towards the end of January Wallace's short term contract with RKO came up for renewal, and though he had been busy working for them, he had precious little feedback - apart from Cooper - as to whether they were happy with his work or not. As he noted in his diary:

It is obvious Wallace was referring here to the draft shooting script, rather than a fully fleshed-out novelisation story for later publication. Wallace and Cooper obviously achieved a lot over those few weeks between the end of December 1931 and the beginning of January 1932, due to the experience of both men in their respective areas of expertise. The fact that Wallace features on the title page of the novelisation and the credits of the film are testament to his initial involvement and the weight of his fame as a writer, even following his death, if not to his actual involvement in the film as finally shot. Nevertheless, a 107 page ‘First Draft Script’ was typed up and presented to RKO on 27 January 1932. That document was titled ‘Kong by Edgar Wallace’ and was very different to the final film with, for example, the ape captive of a circus troupe. An annotated copy of the scenario exists in the Wallace family archive collection. Of course the title was not the truth - it should have read 'Kong by Merian C. Cooper' as that is was it is.

* 1971 – Longanesi, Milano, Italy, 144p. Italian language edition. Note the erroneous sole attribution on the cover to Edgar Wallace.

* 1976 - Newton. Italian edition. Gives sole authorship to Wallace.

References

Campbell, Duncan, Stranger than fiction: the life of Edgar Wallace, the man who created King Kong by Neil Clark – review, The Guardian, 30 July 2015. Available URL: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jul/30/stranger-than-fiction-life-edgar-wallace-king-kong-neil-clark-review.

Clark, Neil, Stranger than Fiction: The Life of Edgar Wallace, The Man Who Created King Kong, The History Press, London, 2015, 256p.

Erb, Cynthia, Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture, 2nd edition, Wayne State University Press, 2009, 336p.

Foster, Alan Dean, Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker, Ballantine Books, 1976.

Glashen, Ray, King Kong Screenplay [webpage], 5 May 2019. Available URL: http://freeread.com.au/@RGLibrary/EdgarWallace/Plays/KingKong.html.

Golden, Christoper, King Kong, Pocket Star Books, October 2005, 374p. Based on the film script by Fran Walsh, Peter Jackson and Phillipa Boyens.

Goldner, Orville & Turner, George E., The Making of King Kong, The Tantivy Press, New York, 1975.

-----, Spawn of Skull Island: The Making of King Kong. Expanded and revised by Michael H. Price and Douglas Turner, Luminary Press, 2002; Midnight Marquee Press, 2019.

Gottesman, Ronald and Geduld, Harry, The Girl in the Hairy Paw, Flare / Avon Books, New York, 1976.

Hilton, James, Lost Horizon (Author’s Edition), Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1937.

King Kong Special, Midi-Minuit Fantastique, October / November 1962.

Lovelace, Delos W., Rear Admiral Byrd and the Polar Expedition, A.L. Burt, New York, 1930, 256p. (Coral Foster pseud.).

-----, King Kong, Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1932, 249p. All known subsequent reprints are listed above.

Morton, Ray, King Kong - The History of a Movie Icon from Fay Wray to Peter Jackson, Applause Cinema and Theatre Books, 2005, 350p.

Mullis, Justin, Kong Count #9 - King Kong (1932) The Delos W. Lovelace Novelisation, Maser Patrol [blog], 2 March 2017. Available URL: https://maserpatrol.wordpress.com/2017/03/02/kong-count-9-king-kong-1932-the-delos-w-lovelace-novelization/.

Ripperger, Walter, King Kong - the last and the greatest creation by Edgar Wallace [serialised in 2 parts], Mystery [magazine], February & March 1933.

The secret is out! Edgar Wallace's last story and how it was filmed, Picturegoer Weekly, London, 15 April 1933.

Vaz, Mark, Living Dangerously: The Adventures of Merian C. Cooper, Creator of King Kong, Random House Publishing Group, New York, 2005, 496p.

Von Harbou, Thea, Metropolis, August Scherl, Berlin, 1926.

Wallace, Edgar, My Hollywood Diary, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1932. Available URL: http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks14/1400821h.html.

Webb, Paul, Edgar Wallace: the thriller writer behind King Kong, The Telegraph, [2005], 1 April 2016. Available URL: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/books/authors/edgar-wallace-the-thriller-writer-behind-king-kong/.

Wikipedia, Delos Wheeler Lovelace, Wikipedia [webpage], accessed 1 January 2020. Available URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delos_W._Lovelace.

-----, Edgar Wallace, Wikipedia [webpage], accessed 2 January 2020. Available URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Wallace.

-----, King Kong (1933 film), Wikipedia, 2020. Available URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Kong_(1933_film).

-----, Photoplay edition, Wikipedia [webpage], accessed 1 January 2020. Available URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photoplay_edition.

Wray, Fay, On the other hand: a life story, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1989, 270p.

--------------------

King Kong 1933 3-sheet poster | Novelisation | Promotional material | Martin Sharp SEX! poster 1967

Last updated: 15 October 2023

Michael Organ, Australia (Home)

Comments

Post a Comment